Note

Generated by nbsphinx from a Jupyter notebook. All the examples as Jupyter notebooks are available in the tudatpy-examples repo.

Asteroid orbit optimization with PyGMO - Optimization

Copyright (c) 2010-2022, Delft University of Technology. All rights reserved. This file is part of the Tudat. Redistribution and use in source and binary forms, with or without modification, are permitted exclusively under the terms of the Modified BSD license. You should have received a copy of the license with this file. If not, please or visit: http://tudat.tudelft.nl/LICENSE.

Context

This tutorial is the third part of the Asteroid Orbit Optimization example. This page reuses the Custom environment part of the example, without the explanation, after which an optimization is executed.

Problem recap

This aim of this tutorial is to illustrate the use of PyGMO to optimize an astrodynamics problem simulated with tudatpy. The problem describes the orbit design around a small body, the Itokawa asteroid.

The 4 design variables are:

initial values of the semi-major axis.

initial eccentricity.

initial inclination.

initial longitude of the ascending node.

The 2 objectives are:

good coverage (maximizing the mean value of the absolute longitude w.r.t. Itokawa over the full propagation).

good resolution (the mean value of the distance should be minimized).

The constraints are set on the altitude: all the sets of design variables leading to an orbit.

NOTE

It is assumed that the reader of this tutorial is already familiar with the content of this basic PyGMO tutorial. The full PyGMO documentation is available on this website. Be careful to read the correct the documentation webpage (there is also a similar one for previous yet now outdated versions here; as you can see, they can easily be confused). PyGMO is the Python counterpart of PAGMO.

Import statements

[1]:

# Load standard modules

import os

import numpy as np

# Uncomment the following to make plots interactive

# %matplotlib widget

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

from itertools import combinations as comb

# Load tudatpy modules

from tudatpy.io import save2txt

from tudatpy import constants

from tudatpy.interface import spice

from tudatpy.astro import element_conversion

from tudatpy.astro import frame_conversion

from tudatpy import numerical_simulation

from tudatpy.numerical_simulation import environment_setup

from tudatpy.numerical_simulation import propagation_setup

import tudatpy.util as util

# Load pygmo library

import pygmo as pg

current_dir = os.path.abspath('')

Creation of Custom Environment

[2]:

def get_itokawa_rotation_settings(itokawa_body_frame_name):

# Definition of initial Itokawa orientation conditions through the pole orientation

pole_declination = np.deg2rad(-66.30) # Declination

pole_right_ascension = np.deg2rad(90.53) # Right ascension

meridian_at_epoch = 0.0 # Meridian

# Define initial Itokawa orientation in inertial frame (equatorial plane)

initial_orientation_j2000 = frame_conversion.inertial_to_body_fixed_rotation_matrix(

pole_declination, pole_right_ascension, meridian_at_epoch)

# Get initial Itokawa orientation in inertial frame but in the Ecliptic plane

initial_orientation_eclipj2000 = np.matmul(spice.compute_rotation_matrix_between_frames(

"J2000", "ECLIPJ2000", 0.0), initial_orientation_j2000)

# Manually check the results, if desired

check_results = False

if check_results:

np.set_printoptions(precision=100)

print(initial_orientation_j2000)

print(initial_orientation_eclipj2000)

# Compute rotation rate

rotation_rate = np.deg2rad(712.143) / constants.JULIAN_DAY

# Set up rotational model for Itokawa with constant angular velocity

return environment_setup.rotation_model.simple(

"ECLIPJ2000", itokawa_body_frame_name, initial_orientation_eclipj2000, 0.0, rotation_rate)

[3]:

def get_itokawa_ephemeris_settings(sun_gravitational_parameter):

# Define Itokawa initial Kepler elements

itokawa_kepler_elements = np.array([

1.324118017407799 * constants.ASTRONOMICAL_UNIT,

0.2801166461882852,

np.deg2rad(1.621303507642802),

np.deg2rad(162.8147699851312),

np.deg2rad(69.0803904880264),

np.deg2rad(187.6327516838828)])

# Convert mean anomaly to true anomaly

itokawa_kepler_elements[5] = element_conversion.mean_to_true_anomaly(

eccentricity=itokawa_kepler_elements[1],

mean_anomaly=itokawa_kepler_elements[5])

# Get epoch of initial Kepler elements (in Julian Days)

kepler_elements_reference_julian_day = 2459000.5

# Sets new reference epoch for Itokawa ephemerides (different from J2000)

kepler_elements_reference_epoch = (kepler_elements_reference_julian_day - constants.JULIAN_DAY_ON_J2000) \

* constants.JULIAN_DAY

# Sets the ephemeris model

return environment_setup.ephemeris.keplerian(

itokawa_kepler_elements,

kepler_elements_reference_epoch,

sun_gravitational_parameter,

"Sun",

"ECLIPJ2000")

[4]:

def get_itokawa_gravity_field_settings(itokawa_body_fixed_frame, itokawa_radius):

itokawa_gravitational_parameter = 2.36

normalized_cosine_coefficients = np.array([

[1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0],

[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0],

[-0.145216, 0.0, 0.219420, 0.0, 0.0],

[0.036115, -0.028139, -0.046894, 0.069022, 0.0],

[0.087852, 0.034069, -0.123263, -0.030673, 0.150282]])

normalized_sine_coefficients = np.array([

[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0],

[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0],

[0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0],

[0.0, -0.006137, -0.046894, 0.033976, 0.0],

[0.0, 0.004870, 0.000098, -0.015026, 0.011627]])

return environment_setup.gravity_field.spherical_harmonic(

gravitational_parameter=itokawa_gravitational_parameter,

reference_radius=itokawa_radius,

normalized_cosine_coefficients=normalized_cosine_coefficients,

normalized_sine_coefficients=normalized_sine_coefficients,

associated_reference_frame=itokawa_body_fixed_frame)

[5]:

def get_itokawa_shape_settings(itokawa_radius):

# Creates spherical shape settings

return environment_setup.shape.spherical(itokawa_radius)

[6]:

def create_simulation_bodies(itokawa_radius):

### CELESTIAL BODIES ###

# Define Itokawa body frame name

itokawa_body_frame_name = "Itokawa_Frame"

# Create default body settings for selected celestial bodies

bodies_to_create = ["Sun", "Earth", "Jupiter", "Saturn", "Mars"]

# Create default body settings for bodies_to_create, with "Earth"/"J2000" as

# global frame origin and orientation. This environment will only be valid

# in the indicated time range [simulation_start_epoch --- simulation_end_epoch]

body_settings = environment_setup.get_default_body_settings(

bodies_to_create,

"SSB",

"ECLIPJ2000")

# Add Itokawa body

body_settings.add_empty_settings("Itokawa")

# Adds Itokawa settings

# Gravity field

body_settings.get("Itokawa").gravity_field_settings = get_itokawa_gravity_field_settings(itokawa_body_frame_name,

itokawa_radius)

# Rotational model

body_settings.get("Itokawa").rotation_model_settings = get_itokawa_rotation_settings(itokawa_body_frame_name)

# Ephemeris

body_settings.get("Itokawa").ephemeris_settings = get_itokawa_ephemeris_settings(

spice.get_body_gravitational_parameter( 'Sun') )

# Shape (spherical)

body_settings.get("Itokawa").shape_settings = get_itokawa_shape_settings(itokawa_radius)

# Create system of selected bodies

bodies = environment_setup.create_system_of_bodies(body_settings)

### VEHICLE BODY ###

# Create vehicle object

bodies.create_empty_body("Spacecraft")

bodies.get("Spacecraft").set_constant_mass(400.0)

# Create radiation pressure settings, and add to vehicle

reference_area_radiation = (4*0.3*0.1+2*0.1*0.1)/4 # Average projection area of a 3U CubeSat

radiation_pressure_coefficient = 1.2

radiation_pressure_settings = environment_setup.radiation_pressure.cannonball(

"Sun",

reference_area_radiation,

radiation_pressure_coefficient)

environment_setup.add_radiation_pressure_interface(

bodies,

"Spacecraft",

radiation_pressure_settings)

return bodies

[7]:

def get_acceleration_models(bodies_to_propagate, central_bodies, bodies):

# Define accelerations acting on Spacecraft

accelerations_settings_spacecraft = dict(

Sun = [ propagation_setup.acceleration.cannonball_radiation_pressure(),

propagation_setup.acceleration.point_mass_gravity() ],

Itokawa = [ propagation_setup.acceleration.spherical_harmonic_gravity(3, 3) ],

Jupiter = [ propagation_setup.acceleration.point_mass_gravity() ],

Saturn = [ propagation_setup.acceleration.point_mass_gravity() ],

Mars = [ propagation_setup.acceleration.point_mass_gravity() ],

Earth = [ propagation_setup.acceleration.point_mass_gravity() ]

)

# Create global accelerations settings dictionary

acceleration_settings = {"Spacecraft": accelerations_settings_spacecraft}

# Create acceleration models

return propagation_setup.create_acceleration_models(

bodies,

acceleration_settings,

bodies_to_propagate,

central_bodies)

[8]:

def get_termination_settings(mission_initial_time,

mission_duration,

minimum_distance_from_com,

maximum_distance_from_com):

# Mission duration

time_termination_settings = propagation_setup.propagator.time_termination(

mission_initial_time + mission_duration,

terminate_exactly_on_final_condition=False

)

# Upper altitude

upper_altitude_termination_settings = propagation_setup.propagator.dependent_variable_termination(

dependent_variable_settings=propagation_setup.dependent_variable.relative_distance('Spacecraft', 'Itokawa'),

limit_value=maximum_distance_from_com,

use_as_lower_limit=False,

terminate_exactly_on_final_condition=False

)

# Lower altitude

lower_altitude_termination_settings = propagation_setup.propagator.dependent_variable_termination(

dependent_variable_settings=propagation_setup.dependent_variable.altitude('Spacecraft', 'Itokawa'),

limit_value=minimum_distance_from_com,

use_as_lower_limit=True,

terminate_exactly_on_final_condition=False

)

# Define list of termination settings

termination_settings_list = [time_termination_settings,

upper_altitude_termination_settings,

lower_altitude_termination_settings]

return propagation_setup.propagator.hybrid_termination(termination_settings_list,

fulfill_single_condition=True)

[9]:

def get_dependent_variables_to_save():

dependent_variables_to_save = [

propagation_setup.dependent_variable.central_body_fixed_spherical_position(

"Spacecraft", "Itokawa"

)

]

return dependent_variables_to_save

Optimisation problem formulation

[10]:

class AsteroidOrbitProblem:

def __init__(self,

bodies,

propagator_settings,

mission_initial_time,

mission_duration,

design_variable_lower_boundaries,

design_variable_upper_boundaries):

# Sets input arguments as lambda function attributes

# NOTE: this is done so that the class is "pickable", i.e., can be serialized by pygmo

self.bodies_function = lambda: bodies

self.propagator_settings_function = lambda: propagator_settings

# Initialize empty dynamics simulator

self.dynamics_simulator_function = lambda: None

# Set other input arguments as regular attributes

self.mission_initial_time = mission_initial_time

self.mission_duration = mission_duration

self.mission_final_time = mission_initial_time + mission_duration

self.design_variable_lower_boundaries = design_variable_lower_boundaries

self.design_variable_upper_boundaries = design_variable_upper_boundaries

def get_bounds(self):

return (list(self.design_variable_lower_boundaries), list(self.design_variable_upper_boundaries))

def get_nobj(self):

return 2

def fitness(self,

orbit_parameters):

# Retrieves system of bodies

current_bodies = self.bodies_function()

# Retrieves Itokawa gravitational parameter

itokawa_gravitational_parameter = current_bodies.get("Itokawa").gravitational_parameter

# Reset the initial state from the design variable vector

new_initial_state = element_conversion.keplerian_to_cartesian_elementwise(

gravitational_parameter=itokawa_gravitational_parameter,

semi_major_axis=orbit_parameters[0],

eccentricity=orbit_parameters[1],

inclination=np.deg2rad(orbit_parameters[2]),

argument_of_periapsis=np.deg2rad(235.7),

longitude_of_ascending_node=np.deg2rad(orbit_parameters[3]),

true_anomaly=np.deg2rad(139.87))

# Retrieves propagator settings object

propagator_settings = self.propagator_settings_function()

# Reset the initial state

propagator_settings.initial_states = new_initial_state

# Propagate orbit

dynamics_simulator = numerical_simulation.create_dynamics_simulator(current_bodies,

propagator_settings)

# Update dynamics simulator function

self.dynamics_simulator_function = lambda: dynamics_simulator

# Retrieve dependent variable history

dependent_variables = dynamics_simulator.dependent_variable_history

dependent_variables_list = np.vstack(list(dependent_variables.values()))

# Retrieve distance

distance = dependent_variables_list[:, 0]

# Retrieve latitude

latitudes = dependent_variables_list[:, 1]

# Compute mean latitude

mean_latitude = np.mean(np.absolute(latitudes))

# Computes fitness as mean latitude

current_fitness = 1.0 / mean_latitude

# Exaggerate fitness value if the spacecraft has broken out of the selected distance range

current_penalty = 0.0

if (max(dynamics_simulator.dependent_variable_history.keys()) < self.mission_final_time):

current_penalty = 1.0E2

return [current_fitness + current_penalty, np.mean(distance) + current_penalty * 1.0E3]

def get_last_run_dynamics_simulator(self):

return self.dynamics_simulator_function()

Simulation settings

[11]:

# Load spice kernels

spice.load_standard_kernels()

# Set simulation start and end epochs

mission_initial_time = 0.0

mission_duration = 5.0 * constants.JULIAN_DAY

# Define Itokawa radius

itokawa_radius = 161.915

# Set altitude termination conditions

minimum_distance_from_com = 150.0 + itokawa_radius

maximum_distance_from_com = 5.0E3 + itokawa_radius

# Set boundaries on the design variables

design_variable_lb = (300, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0)

design_variable_ub = (2000, 0.3, 180, 360)

# Create simulation bodies

bodies = create_simulation_bodies(itokawa_radius)

# Define bodies to propagate and central bodies

bodies_to_propagate = ["Spacecraft"]

central_bodies = ["Itokawa"]

# Create acceleration models

acceleration_models = get_acceleration_models(bodies_to_propagate, central_bodies, bodies)

Dependent variables, termination settings, and orbit parameters

[12]:

# Define list of dependent variables to save

dependent_variables_to_save = get_dependent_variables_to_save()

# Create propagation settings

termination_settings = get_termination_settings(

mission_initial_time, mission_duration, minimum_distance_from_com, maximum_distance_from_com)

orbit_parameters = [1.20940330e+03, 2.61526215e-01, 7.53126558e+01, 2.60280587e+02]

Integrator and Propagator settings

[13]:

# Create numerical integrator settings

integrator_settings = propagation_setup.integrator.runge_kutta_variable_step_size(

initial_time_step=1.0,

coefficient_set=propagation_setup.integrator.CoefficientSets.rkf_78,

minimum_step_size=1.0E-6,

maximum_step_size=constants.JULIAN_DAY,

relative_error_tolerance=1.0E-8,

absolute_error_tolerance=1.0E-8)

# Get current propagator, and define translational state propagation settings

propagator = propagation_setup.propagator.cowell

# Define propagation settings

initial_state = np.zeros(6)

propagator_settings = propagation_setup.propagator.translational(central_bodies,

acceleration_models,

bodies_to_propagate,

initial_state,

mission_initial_time,

integrator_settings,

termination_settings,

propagator,

dependent_variables_to_save)

Optimisation run

From here on out the example is new compared to the Custom environment part of the example.

With the optimization problem and the simulation setup in hand, let’s now run our optimization using PyGMO.

First, we define a fixed seed that PyGMO will use to generate random numbers. This ensures that the results can be reproduced.

Then, the optimization problem is defined using the AsteroidOrbitProblem class initiated with the values that have already been defined. This User Defined Problem (UDP) is then given to PyGMO trough the pg.problem() method.

Finally, the optimizer is selected to be the Multi-objective EA vith Decomposition (MOAD) algorithm that is implemented in PyGMO. See here for its documentation.

[14]:

# Fix seed for reproducibility

fixed_seed = 112987

# Instantiate orbit problem

orbitProblem = AsteroidOrbitProblem(bodies,

propagator_settings,

mission_initial_time,

mission_duration,

design_variable_lb,

design_variable_ub)

# Create pygmo problem using the UDP instantiated above

prob = pg.problem(orbitProblem)

# Select Moead algorithm from pygmo, with one generation

algo = pg.algorithm(pg.nsga2(gen=1, seed=fixed_seed))

An initial population is now going to be generated by PyGMO, of a size of 48 individuals. This means that 48 orbital simulations will be run, and the fitness corresponding to the 48 individuals will be computed using the UDP.

[15]:

# Initialize pygmo population with 48 individuals

population_size = 48

pop = pg.population(prob, size=population_size, seed=fixed_seed)

We now want to make this population evolve, as to (hopefully) get closer to optimum solutions.

In a loop, we thus call algo.evolve(pop) 25 times to make the population evolve 25 times. During each generation, we also save the list of fitness and of design variables.

[16]:

# Set the number of evolutions

number_of_evolutions = 25

# Initialize containers

fitness_list = []

population_list = []

# Evolve the population recursively

for gen in range(number_of_evolutions):

print("Evolving population; at generation %i/%i" % (gen, number_of_evolutions-1), end="\r")

# Evolve the population

pop = algo.evolve(pop)

# Store the fitness values and design variables for all individuals

fitness_list.append(pop.get_f())

population_list.append(pop.get_x())

print("Evolving population is finished")

Evolving population is finishedion 24/24

With the population evolved, the optimization is finished. We can now analyse the results to see how our optimization was carried, and what our optimum solutions are.

Extract results

First of, we want to save the state and dependent variable history of the orbital simulations that were carried in the first and last generations. To do so, we extract the design variables of all the member of a given population, and we run the orbital simulation again, calling the orbitProblem.fitness() function. Then, we can extract the state and dependent variable history by calling the orbitProblem.get_last_run_dynamics_simulator() function.

[17]:

# Retrieve first and last generations for further analysis

pops_to_analyze = {0: 'initial',

number_of_evolutions - 1 : 'final'}

# Initialize containers

simulation_output = dict()

# Loop over first and last generations

for population_index, population_name in pops_to_analyze.items():

# Get population individuals from the given generation

current_population = population_list[population_index]

# Current generation's dictionary

generation_output = dict()

# Loop over all individuals of the populations

for individual in range(population_size):

# Retrieve orbital parameters

current_orbit_parameters = current_population[individual]

# Propagate orbit and compute fitness

orbitProblem.fitness(current_orbit_parameters)

# Retrieve state and dependent variable history

current_states = orbitProblem.get_last_run_dynamics_simulator().state_history

current_dependent_variables = orbitProblem.get_last_run_dynamics_simulator().dependent_variable_history

# Save results to dict

generation_output[individual] = [current_states, current_dependent_variables]

# Append to global dictionary

simulation_output[population_index] = [generation_output,

fitness_list[population_index],

population_list[population_index]]

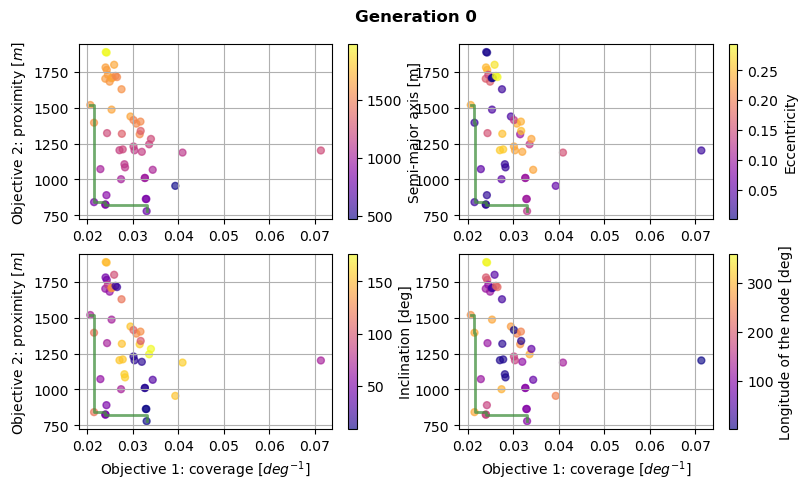

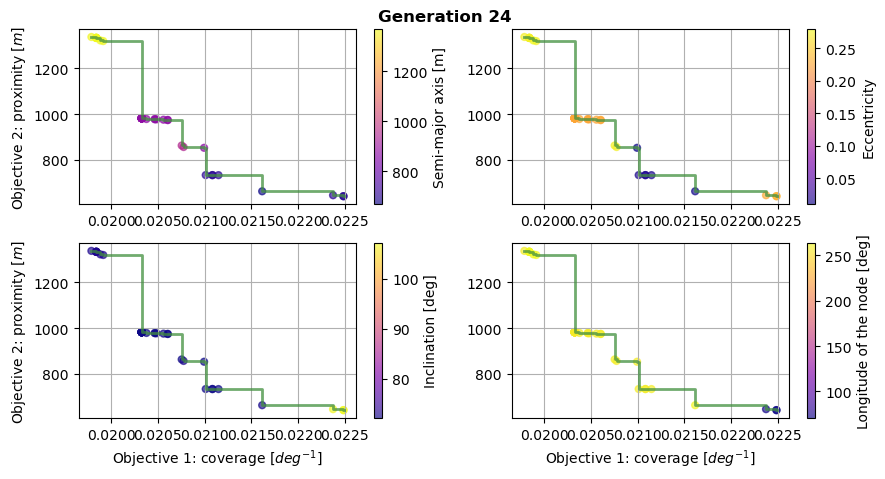

Pareto fronts

As a first analysis of the optimization results, let’s plot the Pareto fronts, to represent the optimums.

This is done for the first and last generation, plotting the score of the two objectives for all of the population members. A colormap is also used to represent the value of the design variables selected by the optimiser. Finally, the Pareto front is plotted in green, showing the limit of the attainable optimum solutions.

These Pareto fronts show that both of the objectives were successfully improved after 25 generations, attaining lower values for both of them.

We can also notice that the population is packed closer to the Pareto front after 25 generations. At the opposite, the population was covering a higher area of the design space for the first generation.

[18]:

# Create dictionaries defining the design variables

design_variable_names = {0: 'Semi-major axis [m]',

1: 'Eccentricity',

2: 'Inclination [deg]',

3: 'Longitude of the node [deg]'}

design_variable_range = {0: [800.0, 1300.0],

1: [0.10, 0.17],

2: [90.0, 95.0],

3: [250.0, 270.0]}

design_variable_symbols = {0: r'$a$',

1: r'$e$',

2: r'$i$',

3: r'$\Omega$'}

design_variable_units = {0: r' m',

1: r' ',

2: r' deg',

3: r' deg'}

[19]:

# Loop over populations

for population_index in simulation_output.keys():

# Retrieve current population

current_generation = simulation_output[population_index]

# Plot Pareto fronts for all design variables

fig, axs = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(9, 5))

fig.suptitle('Generation ' + str(population_index), fontweight='bold', y=0.95)

current_fitness = current_generation[1]

current_population = current_generation[2]

for ax_index, ax in enumerate(axs.flatten()):

# Plot all the population at given generation

cs = ax.scatter(np.deg2rad(current_fitness[:, 0]),

current_fitness[:, 1],

s=100,

c=current_population[:, ax_index],

marker='.',

cmap="plasma",

alpha=0.65)

# Plot the design variable using a colormap

cbar = fig.colorbar(cs, ax=ax)

cbar.ax.set_ylabel(design_variable_names[ax_index])

# Add a label only on the left-most and bottom-most axes

ax.grid('major')

if ax_index > 1:

ax.set_xlabel(r'Objective 1: coverage [$deg^{-1}$]')

if ax_index == 0 or ax_index == 2:

ax.set_ylabel(r'Objective 2: proximity [$m$]')

# Add the Pareto fron itself in green

optimum_mask = util.pareto_optimums(np.array([np.deg2rad(current_fitness[:, 0]), current_fitness[:, 1]]).T)

ax.step(

sorted(np.deg2rad(current_fitness[:, 0])[optimum_mask], reverse=True),

sorted(current_fitness[:, 1][optimum_mask], reverse=False),

color="#418F3E",

linewidth=2,

alpha=0.75)

# Show the figure

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

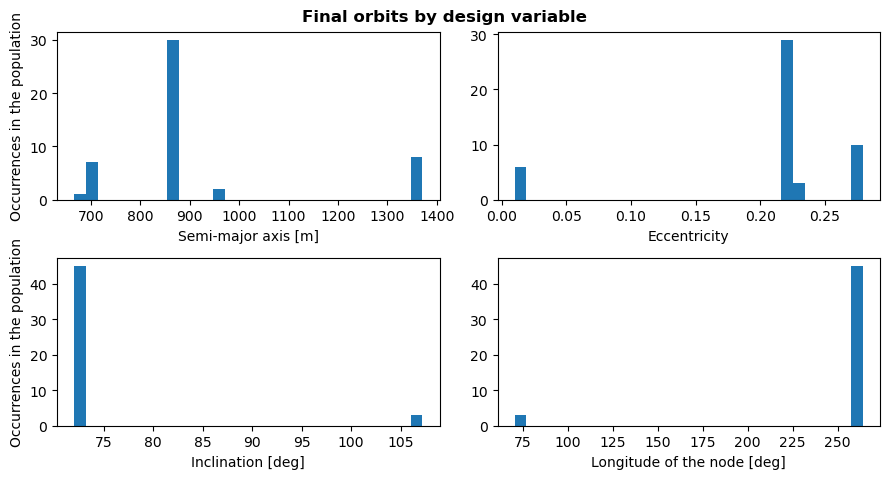

Design variables histogram

Plotting the histogram of the design variables for the final generation gives insights into what set of orbital parameters lead to optimum solutions. Possible optimum design variables values can then be detected by looking at the number of population members that use them. A high number of occurences in the final generation could indicate a better design variable. At least, this offers some leads into what to investigate further.

[20]:

# Plot histogram for last generation, semi-major axis

fig, axs = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(9, 5))

fig.suptitle('Final orbits by design variable', fontweight='bold', y=0.95)

last_pop = simulation_output[number_of_evolutions - 1][2]

for ax_index, ax in enumerate(axs.flatten()):

ax.hist(last_pop[:, ax_index], bins=30)

# Prettify

ax.set_xlabel(design_variable_names[ax_index])

if ax_index % 2 == 0:

ax.set_ylabel('Occurrences in the population')

# Show the figure

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

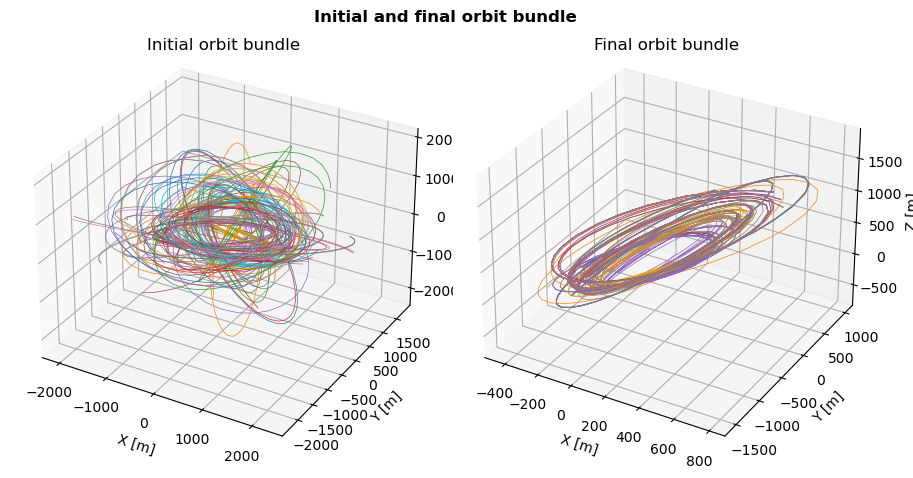

Initial and final orbits visualisation

One may now want to see how much better the optimized orbits are compared to the ones of the random initial population. This can be done by plotting the orbit bundles from the initial and final generations.

The resulting 3D plot show the chaotic nature of the initial random population, where the last generation appears to use a handfull of variations of the similar design variables.

[21]:

# Plot orbits of initial and final generation

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(9, 5))

fig.suptitle('Initial and final orbit bundle', fontweight='bold', y=0.95)

title = {0: 'Initial orbit bundle',

1: 'Final orbit bundle'}

# Loop over populations

for ax_index, population_index in enumerate(simulation_output.keys()):

current_ax = fig.add_subplot(1, 2, 1 + ax_index, projection='3d')

# Retrieve current population

current_generation = simulation_output[population_index]

current_population = current_generation[2]

# Loop over individuals

for ind_index, individual in enumerate(current_population):

# Plot orbit

state_history = list(current_generation[0][ind_index][0].values())

state_history = np.vstack(state_history)

current_ax.plot(state_history[:, 0],

state_history[:, 1],

state_history[:, 2],

linewidth=0.5)

# Prettify

current_ax.set_xlabel('X [m]')

current_ax.set_ylabel('Y [m]')

current_ax.set_zlabel('Z [m]')

current_ax.set_title(title[ax_index], y=1.0, pad=15)

# Show the figure

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

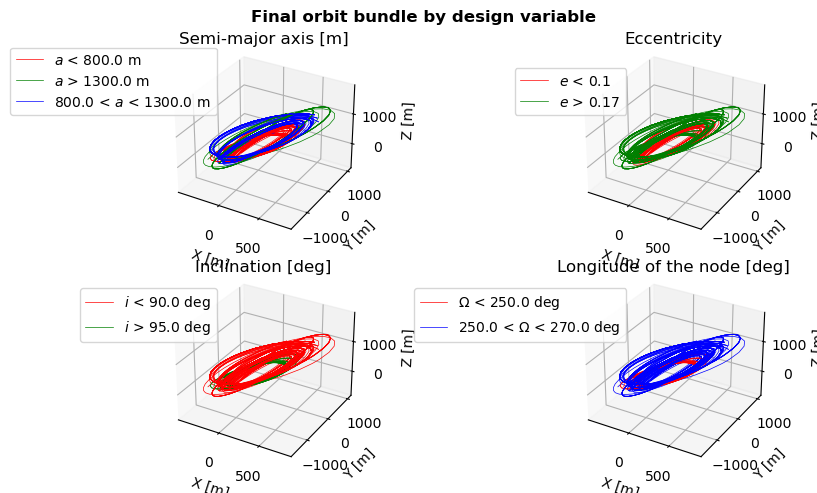

Orbits visualization by design variable

Finally, we can visualize what range of design variables lead to which type of orbits. This is done by plotting the bundle of orbits for the last generation.

This plot one again shows that the orbits from the final population can be sub-categorized into disctinct orbital configurations.

[22]:

# Plot orbits of final generation divided by parameters

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(9, 5))

fig.suptitle('Final orbit bundle by design variable', fontweight='bold', y=0.95)

# Retrieve current population

current_generation = simulation_output[number_of_evolutions - 1]

# Plot Pareto fronts for all design variables

current_population = current_generation[2]

# Loop over design variables

for var in range(4):

# Create axis

current_ax = fig.add_subplot(2, 2, 1 + var, projection='3d')

# Loop over individuals

for ind_index, individual in enumerate(current_population):

# Set plot color according to boundaries

if individual[var] < design_variable_range[var][0]:

plt_color = 'r'

label = design_variable_symbols[var] + ' < ' + str(design_variable_range[var][0]) + \

design_variable_units[var]

elif design_variable_range[var][0] < individual[var] < design_variable_range[var][1]:

plt_color = 'b'

label = str(design_variable_range[var][0]) + ' < ' + \

design_variable_symbols[var] + \

' < ' + str(design_variable_range[var][1]) + design_variable_units[var]

else:

plt_color = 'g'

label = design_variable_symbols[var] + ' > ' + str(design_variable_range[var][1]) + \

design_variable_units[var]

# Plot orbit

state_history = list(current_generation[0][ind_index][0].values())

state_history = np.vstack(state_history)

current_ax.plot(state_history[:, 0],

state_history[:, 1],

state_history[:, 2],

color=plt_color,

linewidth=0.5,

label=label)

# Prettify

current_ax.set_xlabel('X [m]')

current_ax.set_ylabel('Y [m]')

current_ax.set_zlabel('Z [m]')

current_ax.set_title(design_variable_names[var], y=1.0, pad=10)

handles, design_variable_legend = current_ax.get_legend_handles_labels()

design_variable_legend, ids = np.unique(design_variable_legend, return_index=True)

handles = [handles[i] for i in ids]

current_ax.legend(handles, design_variable_legend, loc='lower right', bbox_to_anchor=(0.3, 0.6))

# Show the figure

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()